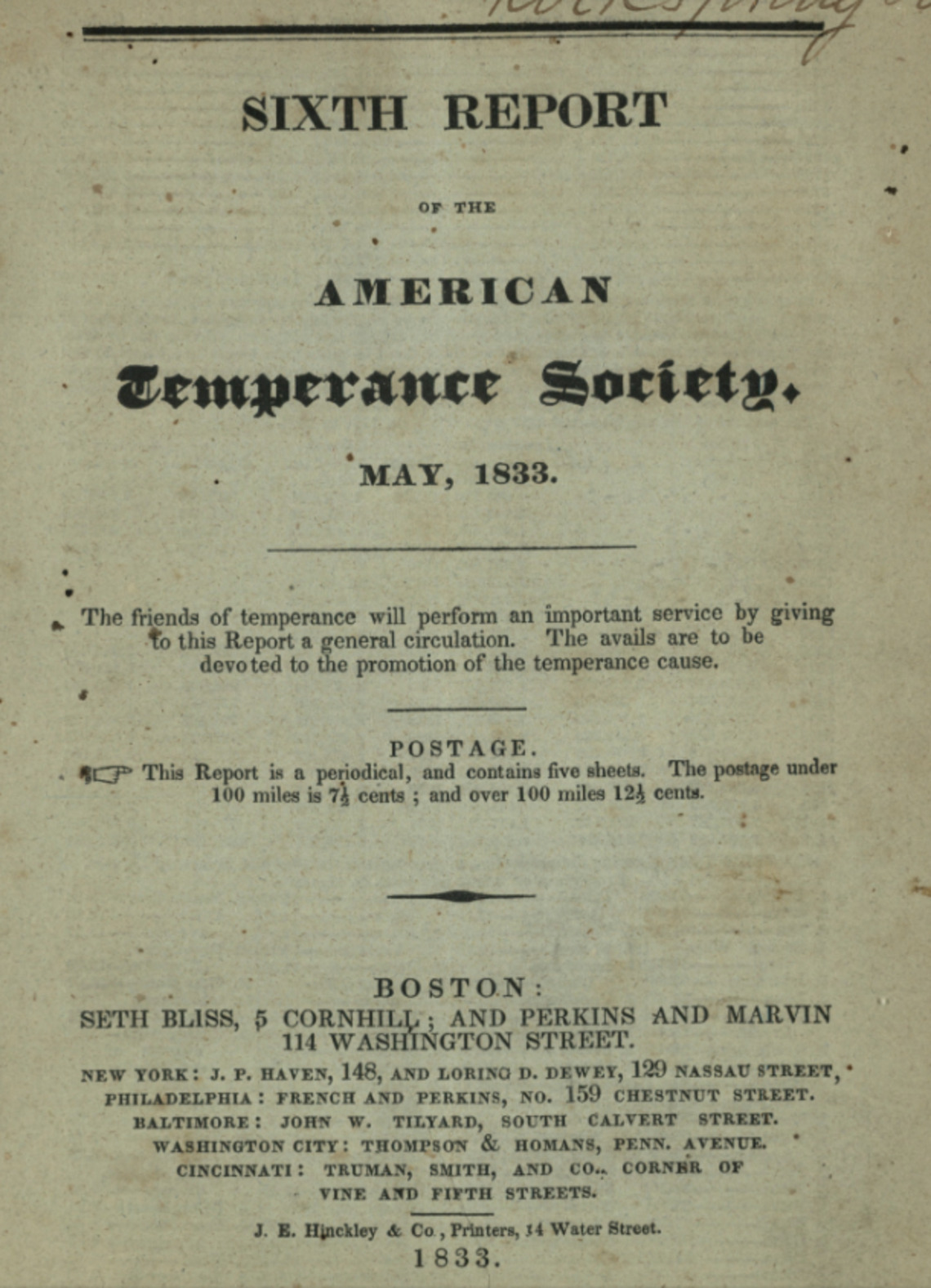

Sixth Report of the American Temperance Society

American Temperance Society

The Unionist 1833-12-19

Unionist content

Transcription

SIXTH REPORT OF THE AMERICAN TEMPERANCE SOCIETY ,

Continued

IV. Laws which authorize the licensing of men to traffic in ardent spirit, violate the first principles of political economy, and are highly injurious to the wealth of a nation.

The wealth of a nation consists of the wealth of all the individuals that compose it. The sources of wealth are labor, land, and capital. The last is indeed the product of the two former; but as it may be used to increase their value, it is considered by writers on political economy, as one of the original sources of national wealth. Whatever lessons either of these, or their productiveness when employed upon each other, lessens the wealth of the country. Capital may be employed in two ways; either to produce new capital, or merely to afford gratification, and in the production of that gratification he consumed, without repealing its value. The first may be called capital, and the last expenditure. These will of course bear inverse proportions to each other. If the first be large, the last must be small, and vice versa. Without any change of the amount of wealth, capital will be increased by the lessened by the increase of expenditure. Although the manner of dividing makes no difference with the present amount of national wealth, it makes great difference with the future amount; as it alters materially the sources of producing it, the means of an equal, or increased reproduction.

For instance, a man fond of noise and excited agreeably by the hearing of it, pays a dollar for gunpowder, and touches fire to it. He occasions an entire loss of that amount of property. Although the powder maker and the merchant, may both have received their pay, if it has not benefitted the man, to him it has been a total loss; and if the sale of it was more profitable than would have been the sale of some useful article, it has been an entire loss to the community. And if by the explosion the man is burnt, partially loses his reason, is taken off a time from business, and confined by sickness to his bed, must have nurses, physicians, &c. the loss is still increased. And if he never recovers fully his health, or reason, suffers his social affections and moral sensibility, becomes less faithful in the education of his children, and they are more exposed to temptation and ruin, and he is never again as able or willing to be habitually employed in productive labor, the nation loses equal to the amount of all these put together. And if his example leads other men to spend, and to suffer in the same way, the loss is still farther increased; and so on, through all its effects.

And even though the powder maker and the merchant have made enormous profit, this does not prevent the loss to the community; any more than the profit of lottery gamblers, or counterfeiters of the public coin, prevents loss to the community. Nor does it meet the case, to say that the property changes hands. This is not true. The man who sold the powder made a profit of only a part even of the money which the other man paid for it; while he lost not only the whole, but vastly more. The whole of the original cost was only a small part of the loss to the buyer, and for the nation. The merchant gained nothing of the time, and other numerous expenses, which the buyer lost; nor does he in any way remunerate the community for that loss.

Suppose that man, instead of buying the powder, had bought a pair of shoes; and that the tanner and the shoemaker had gained in this case, what the powder-maker and the merchant gained in the other; and that by the use of the shoes, though they were finally worn out, the man gained twice as much as he gave for them; without any loss of health, or reason, social affection, or moral susceptibility; and without any of the consequent evils.—Who cannot see that it would have increased his wealth, and that of the nation, without injury to any, and have promoted the benefit of all.

This illustrates the principle with regard to ardent spirit. A man buys a quantity of it, and drinks it; when he would be, as the case with every man, in all respects better without it. It is to him an entire loss. The merchant may have made a profit of one quarter of the cost, but the buyer loses the whole; and he loses the time employed in obtaining and drinking it. He loses, also, and the community loses, equal to all its deteriorating effects upon his body and mind, his children, and all who come under his influence. His land becomes less productive. The capital of course produced by this land and labor is diminished; and thus the means are diminished of future reproduction. And by the increase of expenditure in proportion to the capital, it is still farther diminished, till to meet the increasingly disproportionate expenses, the whole is often taken, and the means of future reproduction are entirely exhausted. And if there is no seed to sow, there is of course no future harvest. This is but a simple history of what is taking in thousands of cases continually; and of what is the tendency of the traffic in ardent spirit from beginning to end. It lessens the productiveness of land and labor, and of course diminishes the amount of capital; while in proportion, it increases the expenditure, and thus in both ways is constantly exhausting the means of future production. And this is its tendency, in all its bearing, in proportion to the quantity used, from the man who takes only his glass, to the man who takes his quart a day. It is a palpable and gross violation of all correct principles of political economy; and from beginning to end, tends to diminish all the sources of national wealth.

About this Item

This is a continuation from previous editions of the paper. Because I cannot tell what The Unionist would have excerpted, I have not included any more of it at this time. This particular excerpt buttresses my published contention that the students at the Canterbury Female Academy were reading advanced philosophy. While I disagree with the political economic analysis forwarded here, it is sophisticated for its time. The meeting of the American Temperance Society was held in May 1833, and the publication came out of Boston. This particular excerpt begins on p. 46 of the pamphlet, near the bottom of the page, through p. 48, most of the way down the page. The full text is online.