Communications [Speech of William Pinkney]

"Humanitas" (pseudonym); William Pinkney

The Unionist 1833-12-19

Unionist content

Transcription

“Mr. Speaker, Iniquitous and most dishonorable to Maryland is that dreary system of partial bondage, which her laws have hitherto supported with a solicitude worthy of a better object, and Citizens by their practice countenanced. Founded in a disgraceful traffic, to which the parent country lent her fostering aid, from motives of interest, but which even she would have disdained to encourage, had England been the destined mart of such inhuman merchandize; its continuance is as shameful as its origin.

Eternal infamy await the abandoned miscreants whose selfish souls could ever prompt them to rob unhappy Afric of her souls, and freight them hither by thousands, to poison the fair Eden of liberty with the rank weed of individual bondage. Nor is it more to the credit of our ancestors that they did not command these savage spoilers to bear their hateful cargo to another shore, where the shrine of freedom knew no votaries, and every purchaser would at once be both a master and a slave.

In the dawn of time, Mr. Speaker, when the rough feelings of barbarism had not experienced the softening touches of refinement, such an unprincipled prostration of the inherent rights of human nature, would have needed the gloss of an apology: but to the everlasting reproach of Maryland, be it said, that when her citizens rivalled the nation from whence they emigrated, in the knowledge of moral principles, and an enthusiasm in the cause of general freedom, they stooped to become the purchasers of their fellow creatures, and to introduce an hereditary bondage into the bosom of their country, which should widen with every successive generation.

For my part, I would willingly draw the veil of oblivion over this disgusting scene of iniquity, but that the present abject state of those who are descended from these kidnapped sufferers, perpetually brings it forward to the memory.

But wherefore should we confine the edge of censure to our ancestors, or those from whom they purchased? Are not we equally guilty? They strewed around the seeds of slavery; we cherish and sustain the growth.— They introduced the system; we enlarge, invigorate, and conform it.—Yes, let it be handed down to posterity, that the people of Maryland, who could fly to arms with the promptitude of Roman citizens, when the hand of oppression was lifted up against themselves—who could behold their country desolated, and their citizens slaughtered, who could brave with unshaken firmness, every calamity of war, before they would submit to the smallest infringement of their rights—that this very people could yet see thousands of their fellow creatures, within the limits of their territory, bending beneath an unnatural yoke; and instead of being assiduous to destroy their shackles, anxious to immortalize their duration, so that a nation of slaves might for ever exist in a country where freedom is its boast.

“Even the very earth itself, (says some celebrated author) which teems with profusion under the cultivating hand of the freeborn laborer, shrinks into barrenness from the contaminating sweat of a slave.” This sentiment is not more figuratively beautiful than substantially just.

Survey the countries, sir, where the hand of freedom conducts the ploughshare and compare their produce with yours.—Your granaries in this view appear like the store houses of emmets [a colloquial word for “ant”], though not supplied with equal industry. To trace the cause of this disparity between the fruits of a freeman’s voluntary labors, animated by the hope of profit, and the slow-paced efforts of a slave, who acts only from compulsion, who has no incitement to exertion but fear—no prospect of remuneration to encourage—would be insulting the understanding. The cause and the effect are too obvious to escape observation.

But it has been said (and who knows but the same opinion may still have its advocates) “that nature has black balled these wretches out of society.” Gracious God! can it be supposed that thy Almighty Providence intended to proscribe these victims of fraud and power, from the pale of society, because thou hast denied them the delicacy of an European complexion? Is their color, Mr. Speaker, the mark of Divine vengeance, or is it only the flimsy pretext upon which we attempt to justify our treatment of them? Arrogant and presumptuous is it this to make the dispensations of Providence subservient to the purposes of iniquity, and every slight diversity in the works of nature the apology for oppression. Thus acts the intemperate bigot in religion. He persecutes every dissenter from his creed, in the name of God, and even rears the horrid fabric of an inquisition upon heavenly foundations.

I like not these holy arguments. They are as convenient for the tyrant as the patriot—the enemy as the friend of mankind. Contemplate this subject through the calm medium of philosophy, and then to know that these shackled wretches are men as well as we are, spring from the same common parent, and endued with equal faculties of mind and body, is to know enough to make us disdain to torn casuists on their complexion to the destruction of their rights. The beauty of complexion is mere matter of taste, and varies indifferent countries, nay, even in the same; and shall we dare to set up this vague, indeterminate, weathercock standard, as the criterion by which shall be decided on what complexions the rights of human nature are conferred, and to what they are denied by the great ordinances of the Deity? As if the Ruler of the Universe had made the darkness of a skin, the flatness of a nose, or the wideness of a mouth, which are only deformities or beauties as the undulating tribunal of taste shall determine the indication of his wrath.

Mr. Speaker, It is pitiable to reflect on the mistaken light in which this unfortunate generation are viewed by the people in general. Hardly do they deign to rank them in the order of beings above the mere animal that grazes the field of its owner. That an humble, dusky, unlettered wretch that drags the chain of bondage through the weary round of life, with no other privilege but that of existing for another’s benefit should have been intended by heaven for their equal they will not believe. But let me appeal to the intelligent mind, and ask, in what respect they are our inferiors? Though they have never been taught to tread the paths of science, or embellish human life by literary acquirements; tho’ they cannot soar into the regions of taste and sentiment, or explore the scenes of philosophical research, is it to be inferred that they want the power, if the yoke of slavery did not check each aspiring effort and clog the springs of action? Let the kind hand of an assiduous care mature their powers, let the genius of freedom excite to manly thought and liberal investigation, we should not then be found to monopolize the vigor of fancy, the delicacy of taste, or the solidity of scientific endowments. Born with hearts as susceptible of virtuous impressions as our own, and with minds as capable of benefitting by improvement, they are in all respects our equals by nature; and he who thinks otherwise has never reflected, that talents however great may perish unnoticed and unknown, unless auspicious circumstances conspire to draw them forth, and animate their exertions in the round of knowledge. As well might you expect to see the bubbling fountain gush from the burning sands of Arabia, as that the inspiration of genius or the enthusiastic glow of sentiment should rouse the mind which has yielded its elasticity to habitual subjection. Thus the ignorance and the vices of these wretches are solely the result of situation, and therefore no evidence of their inferiority. Like the flower whose culture has been neglected, and perishes amidst permitted weeds ere it opens it blossom to the Spring, they only prove the imbecility of human nature unassisted and oppressed. Well has Cowper said—

‘’Tis liberty alone which gives the flower

Of fleeting life its lustre and perfume,

And we are weeds without it.’

About this Item

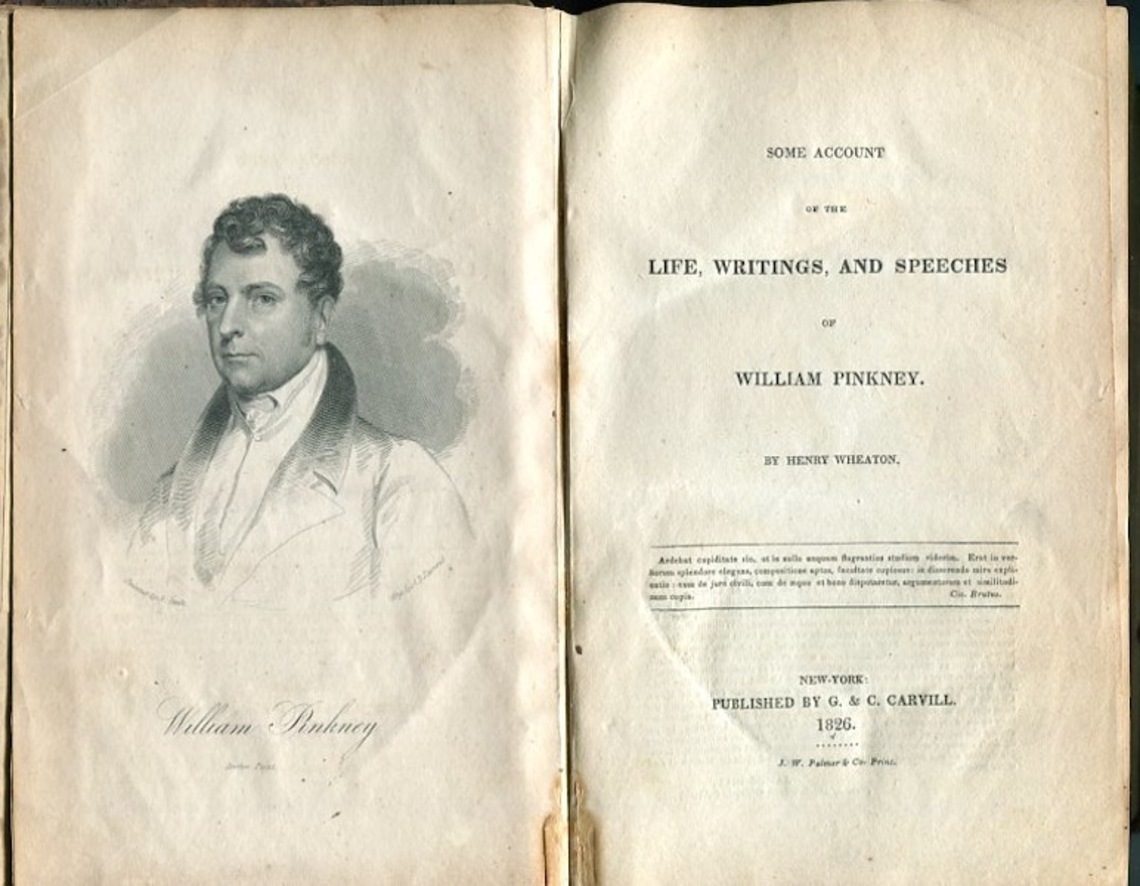

William Pinkney (1764-1822) was an important statesman in the Early Republic. Hailing from Maryland, he served that state in Congress and, at the end of his life, in the Senate. He also performed ably as a diplomat and Attorney General. His reputation as an orator was strong. Pinkney's speech here, from early in his career, was in circulation among the Abolitionists; his fame and his writings were amplified in the 1820s at the time of his death.