Rivers

The Unionist 1833-08-08

Unionist content

Transcription

RIVERS.—There is a wonderous beauty, a mysterious charm, in flowing waters.—Seldom does painter, poet, or novelist, attempt to sketch a scene of surpassing loveliness, but a “smooth stream,” a “murmuring rivulet,” or a “tumbling cascade,” forms a prominent feature in the glowing landscape. Their fair images of human perfection, must chaunt their joys to “babbling brooks”—must sigh out their griefs to an accompaniment of aquatic melody, and “mingle their tears with the torrents as they fall.”

Nor do rivers appear by any means contemptible in the pages of the historian. Who has not heard the fame of the Nile, that source of Egypt, prosperity, and that proverbial emblem of a truly benevolent man? As signs the poet,

“Bounteous as the Nile’s dark waters,

“Undiscovered as their spring.”

And who has not read of the Jordan, which beheld the course and fled backward at the approach of Jehovah’s chosen tribes? Of the Granicus, where the world’s conqueror first met and scattered the countless hosts of Persia? Of the cold Cydnus, which had well nigh checked the rash victor’s headlong career? Of the sacred Ganges, whose waters cleanse from moral pollution? Of the yellow Tiber, that laves the walls of the Eternal City? Of the Rubicon, where the aspiring Roman decided between his ambition and the better feelings of his heart, and threw the torch of civil war among the combustible materials of the old world’s proudest empire?

The traveler who visits lands renowned in ancient story, finds nothing in the relics of their former grandeur, better fitted to impress the mind with that sensation of pleasing sadness which memorials of other days call up, than the broad streams, {unreadable due to a fold} reflected tower, palace, and temple, glittering in the sunbeams, and whose shores echoed to the ceaseless hum of a crowded city’s busy population, where now, solitude, desolation, and silence, reign amid the fallen arches, the broken columns, and the mouldering ruins of structures which the vain architect of former days reared in ponderous and massy strength, as if defying the destroyer Time. How forcibly is he impressed with the vanity of human greatness, as he surveys the quiet stream, rolling on its channel, heedless of the desolation around, unchanged by the mighty revolutions that have swept from the face of day, cities, states, and empires—regardless alike of chieftains, kings, and conquerors, who once dyed its waves with the purple tide of slaughter, or received on its banks the homage of conquered millions, and of the slaves who basely bowed the knee in servile adoration, to the mortal god. The noble Tigris still holds its onward course, unaltered since the haughty walls of Nineveh overhung its banks, and her six score thousand inhabitants who knew not the right hand from the left, listened to the prophet of the Lord warning them of speedy destruction. The famed Euphrates ceases not to flow, though the “queen of cities” is a desert waste, and long ages have elapsed since Chaldea heard the voice of wailing and the loud lament, “Babylon is fallen, is fallen.” Xanthus and Scamander still water the plains of Asia Minor, though the towers of Priam have crumbled into dust, and the bright glory of Ilium has vanished like a vision of the night.

And when the grave in its silence and its gloom shall have closed over all of life and activity the earth now contains; when the grand and beautiful works of art which we behold, shall be as the magnificence of Babylon or of Troy; when we shall have taken up our abode in the cold chambers of darkness, “and the places that now know us shall know us no more;” when our names shall fall on the listener’s ear like the faint echo of a distant voice, or the dim recollections of a half forgotten dream; when the finger of decay shall have erased the records of our achievements, and our deeds shall be remembered as the traditionary legends of antiquity; when the generations that succeed us shall have faded from the earth like the passing shadow of a thin and fleecy cloud; the lovely streams by which we delight to rove, will still wind through the vallies [sic], diffusing verdure and fertility in their path; the cataract will still leap “in thunder and in foam,” from the rocky brow of the precipice, sending up its sparkling spray to glitter in the dazzling sun-light, and to crown its front with a halo of varying and respondent hues; the calm and stately current of the might river will still sweep on in majesty to the ocean, shaded perhaps by the thick boughs of the giant oak or gloomy pine, and fringed with shrubs and blooming wild flowers, where we behold reflected in its pellucid mirror, the spire of the village church, and the thickly crowded habitations of men; and where now it visits but the forest haunts of roving savages and beasts of prey, or glides through glens untrod by human footsteps, and undisturbed by voice or sound, save the ripple of the waters below & the rustle of leaf and branch above, shall then be seen the snow-white sail wafting along its tranquil tide the rich product of agricultural industry and commercial enterprise.

A new race shall have risen to possess the heritage of their fathers, to walk among the ruins of our splendid edifices, to gaze on the streams that we admire, and while they gaze, to muse as we do now, and as hundreds before us have done, on the fleeting evanescence of earthly fame, and the shadowy illusiveness of human grandeur.

“So passes this world’s glory.”

We, the People.

About this Item

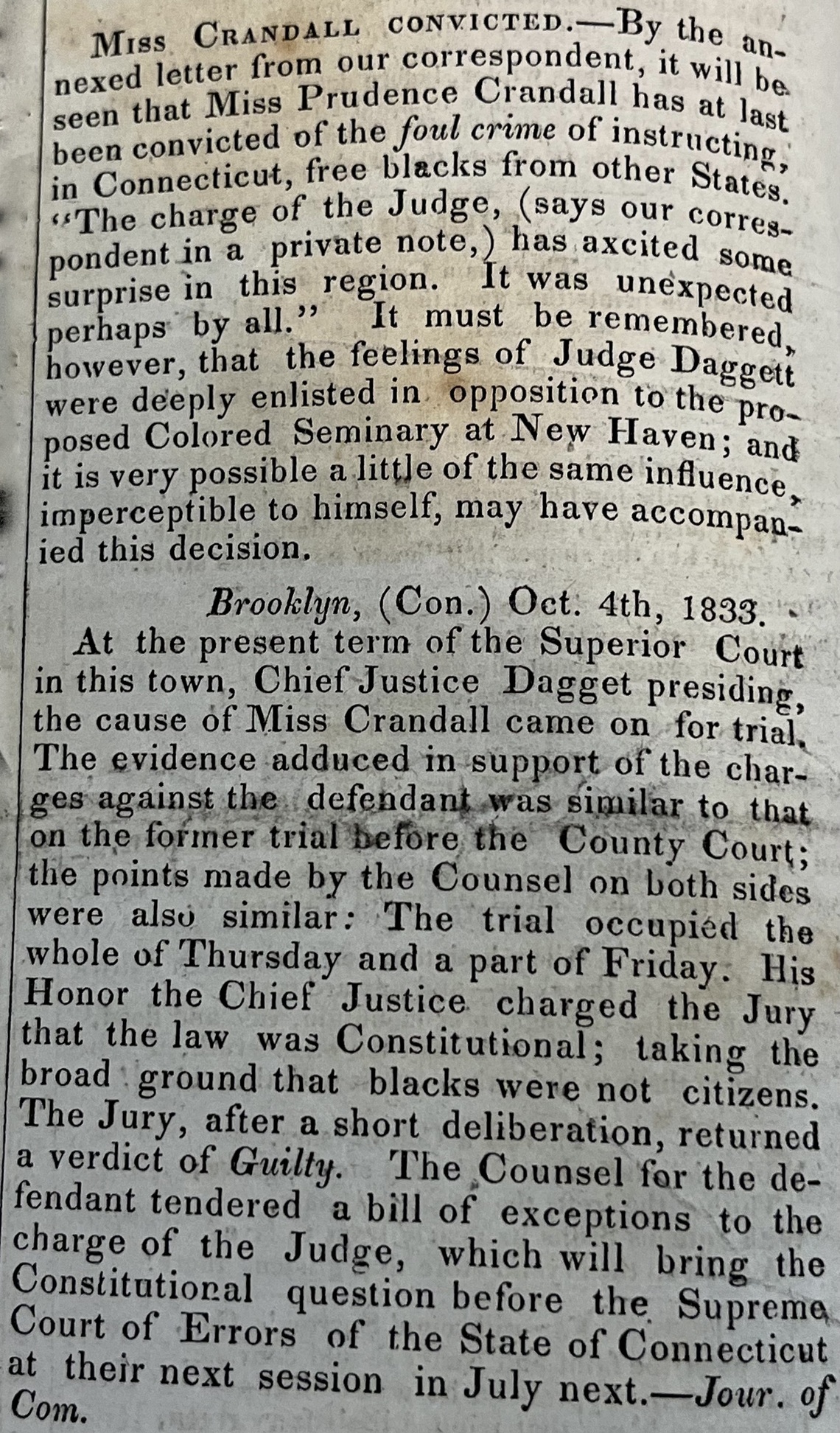

This newspaper, We, the People is one for which Charles C. Burleigh briefly worked. They would prove to be a strong ally to the cause, as can be seen here in the accompanying story from their October issue.