Samuel J. May's response to Adams and Judson Circular

Samuel J. May

The Unionist 1833-08-08

Unionist content

Featured Item

Transcription

TO RUFUS ADAMS, ESQ.,

AND ANDREW T. JUDSON, ESQ.

Gentlemen: I presume that the foregoing communication contains a statement of the case, between yourselves & Miss Crandall, as favorable to yourselves, as you were able to make. The request to all the Editors of newspapers in the state, that they would republish the article is proof sufficient of the estimation in which it is held. Still, gentlemen, it appears to me to be any thing but an exculpation of yourselves. This I shall now attempt to show.

You evidently intend it should be believed, that Miss Crandall gave the citizens of Canterbury just cause of offence, at first, in having so soon discontinued the instruction of their daughters. The charge has indeed been explicitly brought against her in another periodical (“the Colonizationist No. 2”) in a letter from Canterbury, written very probably by one or the other of yourselves. It is there stated, that she “made numerous and solemn engagements with the citizens of Canterbury, that if they would aid her in the establishment of a school, she would continue the school for their children. “These engagements” says the letter-writer “she has violated without excuse.” If you could prove all this, Gentlemen, you would certainly prove that she did very wrong, but not that you have done right.” I will venture to say however, that if she had given up the office of an instructress altogether, we never should have heard a syllable about her “numerous, solemn engagements.” And discontinued the instruction of your children, if she had not first been threatened with the loss of your patronage, unless she dismissed from her school a colored girl, whom she thought it her duty to educate.† Now, gentlemen, if it be true, as you assert, that you and your neighbors are not opposed to the education and kind treatment of colored people, if you really desire to see them free and happy, why was Miss C. threatened with loss of patronage if she permitted Sarah Harris to continue as one of her pupils? You tell your readers that the common schools in your town admit colored children to equal privileges with white ones, and that you rejoice that they do so. Why then did you not rejoice that Miss Crandall admitted a colored girl into her school? Why! unless you chose that the children of colored people should enjoy the blessings of education, only in a very stinted measure? Answer me this if you please?

Again. You complain, and have elsewhere complained that Miss C. made the change in her school abruptly—that she did it without asking the consent or even the advice of her former patrons. I apprehend that the blame for this must attach to yourselves rather than to her. If you had ever evinced, that interest in the education and freedom and happiness of our colored brethren, which you now profess to feel, there can be little doubt that she would have disclosed to you her feelings and her purposes; and gladly have availed herself of your assistance. But she perceived that you, like most of our white brethren, regarded the colored children of our Heavenly Father as doomed to degradation, and not to be admitted to equal privileges even in this land of boasted liberty. Therefore she did not reveal her plan until it was matured. She anticipated that you would oppose it. The event has proved that she judged correctly.

But you assure your fellow-citizens, and have made the declaration before, that the main ground of your opposition to the school, has been and is that you know certain erroneous principles were to be inculcated there. What those principles are, you have not stated. You assert that they are very dangerous—thinking perhaps that you may thus frighten the community into the belief that your persecution of Miss Crandall has been altogether reasonable, and praiseworthy. Have not the enemies of truth, and freedom, and the Gospel in all ages pursued a similar course? Let us see how you have proceeded.

Miss Crandall advertised in several newspapers, that she would receive into her family “young ladies and little misses of color” and give them instruction in certain branches of knowledge, which she specified. You and others in the village were offended at her proposal. And I venture to say that no one of you will deny that the real ground of your offence was, that her pupils were to be colored girls. If her proposals had been to receive into her family “young ladies and little misses” from New-York and Boston and other cities, whose parents would be able and willing to pay more liberally for their education, than we in the country are accustomed to pay for ours. I suppose not one of her neighbors would have dreamt of denying her the right to do so. It was then without doubt the color of her pupils, that was the whole ground of the objection made at first to her school. Instead however of frankly acknowledging this—acknowledging that you are unbelievers (practically at least) of the great truth that all men are created equal, and have an unalienable right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness—instead I say of frankly acknowledging your unbelief or your dislike of this truth, as the ground of your opposition, you have gone about (like the opposers of human improvement in all ages) to make it generally believed that the school was established for purposes very different from those avowed in the advertisement. You have tried to awaken the apprehension that the existence of such a school will be directly or indirectly most dangerous to the peace, and welfare of the country. And you now set this forth as your principal objection to the school.

How should you, gentlemen, like to be dealt with in this mode? How would Col. Judson like to find his neighbors opposing his location in their village, on the presumption, that he had set up his office there, for other purposes than those of his profession—on the presumption that he came there to disseminate certain pernicious doctrines in politics or religion? How would he like it, if he found the people of Canterbury combined to make him discontinue his practice as a lawyer, or leave the town, because he is known to be a freemason. If his neighbors should succeed in diffusing unfriendly feelings towards him throughout the town, and at length procured a general meeting of the inhabitants to express their unqualified disapprobation of his purpose to continue as a lawyer among them, what would he think, what would he say, if after having heard himself accused of holding and intending to disseminate pernicious principles, his fellow citizens should refuse his permission to be heard in explanation and defence of his real views and purposes? Would he not cry out against the unrighteousness? Gentlemen, you must reverse the case, if you would see how your conduct appears to many, and will appear to many more.

That some of Col. Judson’s principles are actually bad, dangerous to the peace of Society &c. has now become most notorious. For has he not been laboring from the first to prevent the dissemination of what he believes to be erroneous and dangerous opinions, not by showing them to be erroneous, but by exciting the popular prejudices, and calling for the interference of the civil arm? And is there any principle, which has wrought more mischief in the world that this? All history answers, No.

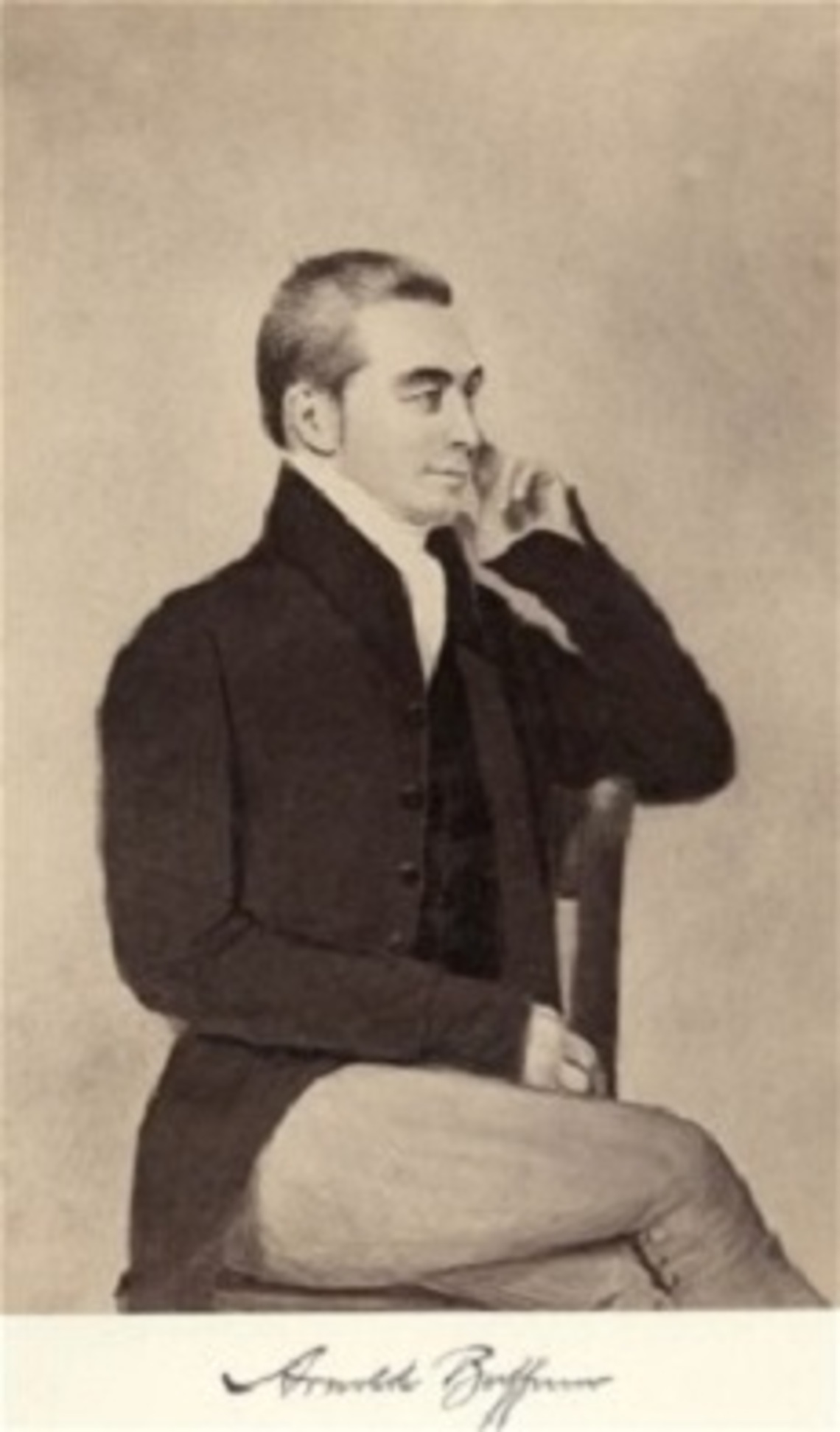

In this connexion, I will notice a false accusation which you have again brought against me. You accuse Mr Buffum and myself of pouring out threats upon the town and inhabitants. The same charge you alleged more explicitly against us in the Norwich Republican of March 27 th . But you have never informed the public what those threats were.—Nor can you. None were uttered. I now declare, that I heard not a word from Mr Buffum in the tone or spirit of threat; and that not a syllable of the kind escaped my lips. I call upon you to contradict me if you please—and make your contradiction good if you can.

You have taken no little pains, gentlemen, in your communication, & on other occasions, to make it appear as if you and the people of Canterbury are the injured, suffering party. That you may have suffered some injury in the course of the unhappy collision, which you have awakened, is possibly true. But that any injury, any disregard to your rights and feelings was intended in the establishment of Miss Crandall’s school on its present plan, there is not the slightest reason to suppose. I can most solemnly declare, that from the first I have been willing to treat even your prejudices with some consideration. Witness my letter to Miss Crandall, dated Feb. 28 th , written so soon as I heard of the opposition you were preparing to make to the prosecution of her plan. If I had been permitted to speak for her at your town meeting, as she requested I might be permitted to do, you would soon have learnt that neither Miss C. nor her patrons had any wish to force the continuance of her school in your village. They were, and I trust still are, willing to have it removed to any suitable place, that might be obtained for it. In a conversation with Col. Judson a few days after the meeting, I gave him this assurance distinctly; as he doubtless remembers. His reply I shall never forget. ‘No,’ said he, ‘that school shall not be located in any part of the town of Canterbury; no—not in part of the State of Connecticut. I will get a law passed,’ he continue, ‘by our next Legislature, prohibiting the introduction of colored from other States into this for the purpose of attending school.‡ I can obtain thirty thousand signers to a petition for such a Law.’ The same overbearing, tyrannical spirit was conspicuous in that gentleman’s language and manner, at the town meeting; and has been too apparent in many of his doings since. To protect, if I may be able a lone woman from the operations of such a spirit, I have felt it my duty to stand with others between her and her oppressors. If she has done wrong, or spoken unadvisedly, let her be rebuked. I would not attempt to justify her error. But she has rights, and they must be respected. If her location in your village is disagreeable to you, and you can enable her to procure suitable accommodations elsewhere, I for one should advise her to remove, & I believe all her patrons would concur in the advice. But your attempt to compel her to abandon her school, we regard as a flagrant violation of her privileges as an American citizen, and we have therefore advised her to resist, peaceably but firmly. The law which you have procured from our last Legislature, we are confident is unconstitutional, and have been so advised by able civilians.—We have therefore thought it best for Miss C. to continue her school, until the validity of that Law shall have been ascertained. If it shall be found to be indeed a good and a valid law of Connecticut, then of course Miss Crandall and her patrons will peaceably abide the consequences of her violation of it. Her school must be abandoned; and it must then be acknowledged before the world “that all men are not permitted to enjoy their unalienable rights even in New-England."

I have more to say in reply to your communication; and shall resume my remarks next week; when I shall particularly notice the charge so often repeated by you, that false and dangerous principles are to be taught at Miss C’s school.

SAMUEL J. MAY

*To preclude the possibility of an inference that the truth of this accusation is admitted, we would simply express our conviction that Miss C. has made no engagements, of which the discontinuance, or the change of her school could be considered a violation. She went to Canterbury, at least as much to confer a favor as to receive one, and was never under any more obligation to teach the children of that village, than are the merchants there to sell their goods to her or others, nor did she suppose the people of Canterbury to be obligated to send their daughters to her school, more than they were, or than she was, to purchase the commodities offered by those merchants.

† See Miss Crandall’s Letter published in the Advertiser of May 9 th .

‡ Col. Judson in the earnestness of his determination to overthrow Miss Crandall’s school, threatened that there should also be a clause in his Law, by which the colored people in the State should be restrained within the towns to which they now belong, so that even their children could not be sent to Miss C. for instruction. But it seems that for some wide reason he has since concluded to omit the proposed clause.

About this Item

Samuel J. May's response to Judson and Adams contains extensive primary evidence about the genesis of the Canterbury Female Academy.