“Circular of Messrs Adams and Judson"

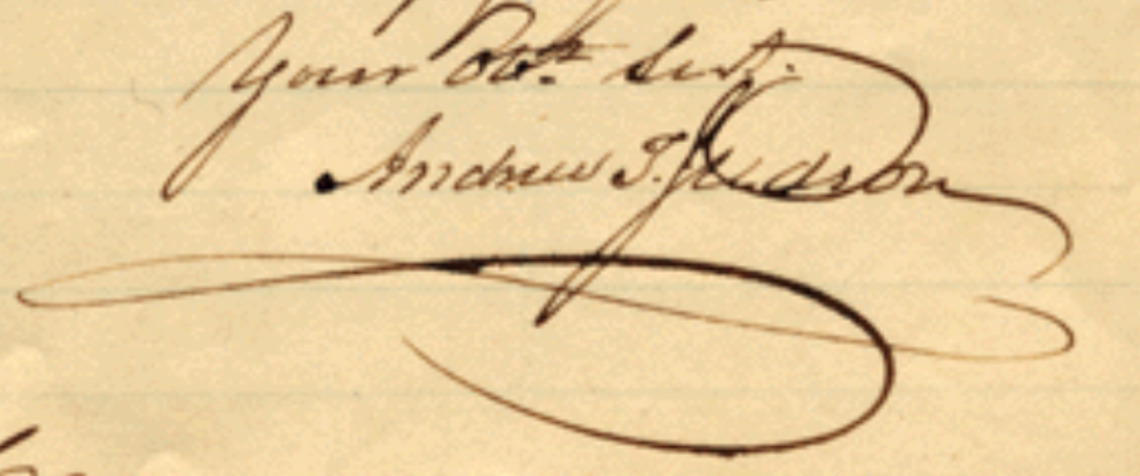

Rufus Adams, Andrew T. Judson

The Unionist 1833-08-08

Unionist content

Featured Item

Transcription

Canterbury, CT. July 19, 1833

CIRCULAR OF MESSRS ADAMS AND JUDSON.

CANTERBURY, CT. July 19, 1833

It may be due the public, as well as ourselves, and the town in which we reside, that a concise answer should be made to some of the most prominent aspersions cast upon us, and our fellow citizens, in connection with the subject of a school set up in Canterbury for “colored misses.” We had supposed that the principal facts were understood by the community, so that any exaggerated statements, false accusations, or artful insinuations, would find no resting place in the mind of any honest man. Lest it may be supposed that we acquiesce in these numerous and perverted statements, we think proper to present for consideration, a few circumstances, trusting that those who know us, will not so readily receive for truth, the assumptions of those who have so liberally bestowed so great a variety of epithets upon us.

PRUDENCE CRANDALL came here with a proposition to remove her School from Plainfield to this place, and establish one here, for the instruction of Young Ladies. The citizens of Canterbury readily embraced the offer, and gave her their patronage. The School, continued from the Fall of 1831, until January or February, 1833. At that time, as we have since learned, Miss C. was proselyted to the immediate Abolition faith. She started for Boston under a fictitious pretence, and saw Mr. Garrison, the leader of that party. She returned home and immediately went to New York and came back, as she told us, with an engagement and under a contract, to receive into her school, twenty colored girls, with an expectation of increasing the number to the full extent of her accommodations. The dismission of her former school, and the announcement of this new project, was the first knowledge given to those who had patronized her. It was soon ascertained upon what ground the school was to be established, and what principles were to be inculcated. The levelling principles of the immediate abolitionists, had taken full possession of her mind, and it was soon made known to us, who were to be the patrons of the school. When we saw Arnold Buffum, and others associated with him, assert what they denominated her rights, and when their threats were poured out upon the town, and all its inhabitants, we could anticipate the ultimate effects upon the town.

We distinctly state to all who may feel an interest in this matter, that we are not opposed to the education and kind treatment of the colored people. It is not in the power of any man, in truth, to say, that we have ever ill-treated a person of color. We desire to see them free and happy. This is the universal sentiment of the inhabitants of the town, so far as we know it. Our schools admit colored children to equal privileges, and we rejoice that they do so. Those schools are all visited and are under the superintendence of proper boards, excluding all danger, from the inculcation of erroneous principles. The law now in force, makes schools for foreign blacks subject to the assent of the civil authority and select men of each town, so that it is an easy matter to have such a school now, provided that board could be satisfied that no pernicious principles are to be inculcated, and no danger could arise to the town or state. Is not this right? Why should any person desire to force upon any community, a school of any sort, against all their wishes? Have the inhabitants no right to be heard in reference to the location of such an institution among them, and more especially when they know the dangerous consequences to which such measures would tend? Are the people of this State ready to admit that the abolitionists, as they are called, are diffusing sentiments and opinions consistent with the constitution and the peace of society? Is there any individual in the State of Connecticut, who would feel willing to have such a school. Together with all the necessary evils, situated within his own town or village? The answer, will be, no. Then let the same feeling be extended to us. This is the only way to ascertain whether the town of Canterbury has done right or wrong. The distinct objection which has been made by the inhabitants of the town, to the location of this school within its limits, consists in the dangerous tendency of the principles pressed by the abolitionists wherever they go, in language peculiar to themselves.—These principles are well understood, and it would be with deep regret, that any school should be established and continued, for their advancement, in a community where our friends are compelled to reside.*

The manner in which Miss C. effected the change in her school, was very objectionable, and no friend that we have met with, can furnish any justification. We know of nothing that could have been done by the town, that has not been done, to induce her to remove the school, to some place where there were no objections. She has been urged by individuals—and entreated by committees, who have waited upon her, to give up this location of her school. We have heretofore stated, and we now repeat it that we offered to take the house at the price she had contracted to pay for it, and relieve her from any loss on that account. This was declined, and then the town petitioned the General Assembly, and the law which she, with the advice of her friends, now resists, was passed. Nearly a month after the rising of the Legislature, she was notified that a suit would be commenced by the Grand Juror. At the trial, her counsel gave in a demurrer to the complaint, admitting the facts true, and submitted to the finding of the court without argument. The Court required her to give bonds of $150 to appear at the net Court, which she refused to give.—This she had a right to do, and be committed if she chose. No one will say that she could not have given the bond on the spot. But it had been agreed before hand, by those who directed her what to do, that she should go to jail. She went and staid as long as suited her purposes, less than 24 hours, and then gave the bond. Some person has put in wide circulation, the story that she was confined in the cell of Watkins the murderer. This is part of the same contrivance to “get up more excitement!” She never was confined in the “murderer’s cell.” She was lodged in the debtor’s room, where every accommodation was provided, both for her and her friends, whose visits were constant. She was confined no where else. It is said in justification of this untruth, that Watkins, some of the last days of his life, was taken out of his cell to receive the clergy and his friends, in the debtor’s room, because it was more convenient. How does that accord with the statement made? Just as well might it be said by those who go into the meeting-house, where Watkins attended meeting some of his last Sabbaths, that they had been in the “murderers cell.”

Does any one think or believe that this school, with all its evils, should be fixed, and permanently located here, we will just ask them to consider the manner too, in which this has been pressed upon us, by foreigners or persons residing out of town and State. If they are actuated by the pure principles of benevolence, how much more of that virtue they would evince to the world, by taking the school home to the places of their own residence. What necessity is there to bring persons from New York, or Philadelphia, to Canterbury? They certainly can be educated there quite as well, and more especially if we are so much like barbarians as is pretended. We wish this to be well considered, before blame is cast upon the town of Canterbury. Is not the peace and safety of community, of consequence? It will not be understood that the town ever entertained any danger from the girls themselves, but every person must know that many others will of necessity, be drawn around this nucleus, and connected with the principles of the abolitionists, who will not say that our habitations, our persons and our peace, will be insecure? In answer to this question, we will exhibit to the public, some of the principles,—some of this christian benevolence,—some of this milk of human kindness, extended to us. During the last week, the “Climax” has been circulated, and sent us from the Post office in New York, marked with double postage, when the gentleman from whose press it issued, might as well have brought it himself to us, as to others. We unequivocally say, the ”Climax” is a wanton perversion of truth.

We will invite the reader to go one step further. We have received through the Post Office, from some zealous abolitionist, a tract, upon which is ingeniously written, in connection with the title of the tract, so that when taken together it reads as follows—viz:

“Thus saith the Lord, consider your way.

The Eternal Misery of Hell: this place is for whom?

For Judge Adams and A.T. Judson.”

If the reader will not be wearied, one other specimen of this benevolent work, which is going on to coerce this State into these Christian measures, as they are denominated, shall also be exhibited to public view. On the 18 th inst., one of the signers of this communication had delivered to him by the Post Master, a letter mailing in Pittsburg, Penn. July 12, in the following language:

‘Pittsburg July 10, 1833.

“Disgraceful Scoundrel—I have just read in the Boston Advocate, that you have had a white young lady put in prison, for taking in her school some colored girls. From all that I have seen and heard of your conduct in this matter, I must say my opinion of you is this—You is (are) a poor, dirty, mean, pitiful, dastardly puppy. Hypocritical villain, a rascal of the lowest order. I cannot or will not waste any more paper with such a Hell deserving hypocrite as you is. (are.) But this much I will tell you, I will be in Canterbury in 3 weeks, and you may prepare yourself for me, for I mean to beat you under the earth, if I can lay my hands on you. If not I will take a shot at you. You poor dead dog.”

“N.B. If you don't change your course of life and conduct towards that good young woman, in case I do not meet with you myself, I will hire some Irishman to mould you. It shall be done if I have to [pay] five hundred dollars to have it done.”

“I leave you a poor Devil. G.P.”

“The name of the young lady is Miss Prudence Crandall. At the advice of a friend, [I] erase my name, as I shall be in your little Hell.”

Fellow citizens, such is the temper, and such the means employed, to fasten upon this town, and its inhabitants, an institution of benevolence. When it shall be fastened here, what will be the effect? We leave them to the sober judgment of reflecting men.

RUFUS ADAMS.

ANDREW T. JUDSON.

*The charge implied in this sentence, is a FALSE ACCUSATION. It is also a recent one, and has never to our knowledge been publicly made before, except on the 4 th of July last, when it was met with a prompt denial of its truth.

About this Item

The circular of Judson and Adams is a revealing document. Outraged and petulant in tone, they complain about receiving hate mail, about Crandall's support from out of state, and about the content of the school inculcating Abolitionist ideas. They give away their ultimate position when they ask "Does any one think or believe that this school, with all its evils, should be fixed, and permanently located here(?)"