Popular Education, Politically Considered

unknown

The Unionist 1833-08-08

Unionist content

Transcription

POPULAR EDUCATION,

POLITICALLY CONSIDERED.

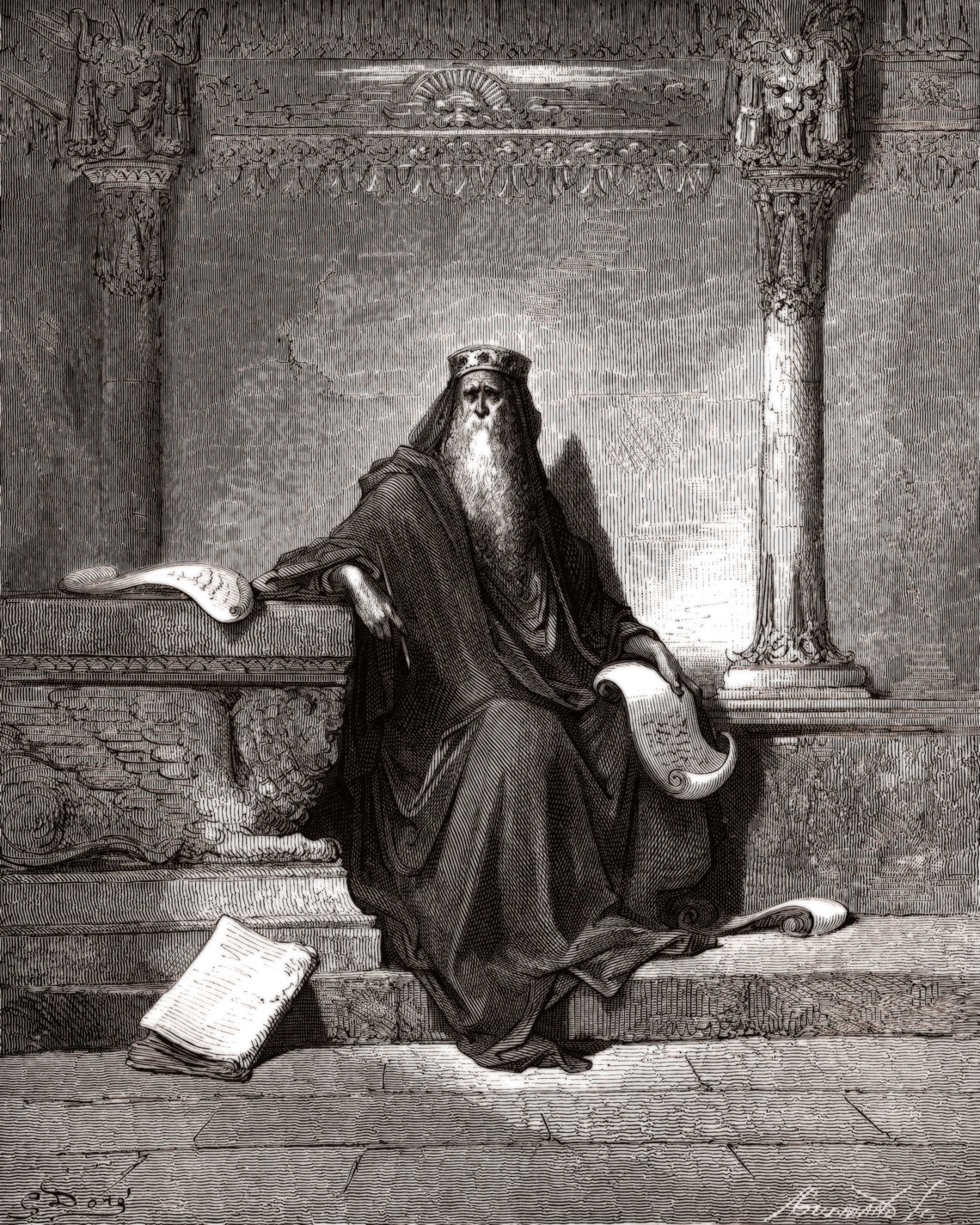

Allowing what we are so continually boasting about, that more information is universally diffused among us than among any people on earth, and that all are at liberty to acquire knowledge to any extent, still it cannot be denied, that there is prevalent a great deal of ignorance on many subjects of paramount importance. It is nothing to the purpose—it is no consolation whatever to insist, that still we are superior in this respect to other communities. The only question for us to consider is—whether the people of this country have as much knowledge, as is indispensable to their temporal and eternal well-being—their social or individual happiness? Whether there is no need of earnestly reiterating every where among then the exhortation of the wise man “get wisdom, get understanding?”

I am well aware that much is said about the necessity of a general diffusion of knowledge to the preservation of our political constitution. But in respect to this point alone, I question if there be common among us a clear perception, and deep feeling of its importance. Else why is it that in many of our States scarcely any provision, and in some none whatever, is made for the instruction of youth; and that even in those States, which have long been applauded for the great number of their schools, a large proportion of these have ever been and still are inadequate to the purpose for which they were instituted. Though we have in New England much of the form of public education, the reality is generally wanting. Very few, in comparison with the whole number of those who attend our common schools, very few leave them possessed of those elements of good learning, which it is pretended are taught there. Very few indeed who can write their thoughts on any subject with propriety and ease; and not many more who can read the thoughts of others with facility and pleasure. Most that is really acquired at these schools, even by those who make the best use of the advantages afforded in them, is a sort of verbal acquaintance with three or four elementary sciences. They do not acquire there the use of the higher powers of mind—thinking, reasoning, judging—and our youth, excepting in the few instances of those who receive good instruction at home, go forth into the world, mingle in the collisions, and assume more or fewer of the offices of society without knowing how to distinguish between many things that differ essentially. They at once fall into the ranks of this party or that, and are content to swell the number of those, who cry out for one popular leader or another—for this system of measures or that.

Although we often hear it said, an every body concurs in the sentiment, that a federal republic cannot long be maintained unless the people generally are well informed, yet I ask what school, yes what single school can be named, where the great principles of civil government are taught, and the peculiar characteristics of our Federal constitution. These, like all other great principles, are simple, and not hard to be understood, unless, the mind has been warped by a regard to sectional interests, or the schemes of a faction.—What young man of common sense might not easily be made, even before he leaves school, to understand these things perfectly? And if all young men were, as they should be, thus taught, moreover made to realize deeply their individual responsibilities as freemen, how difficult would it be to make them the creatures of a party, and to impose upon them as is continually done by factious men. But instead of this, how true it is, and sad as it is true, that most of our young men are left to learn all they are to know of political science, and of their own duties as members of a great Republic, amidst the contests of rival factions, and from those whose opinions have been warped by sectional interests and party passions.

Let it not be said, that I would impose upon the private citizen a degree of knowledge, which it can be needful only for pubic functionaries, or men of great influence in the community to possess. Let it not be objected, that I am urging the example even of a king upon every one, who hears me. Let it not be urged, that Solomon had a need of great wisdom which any of us have not; and that it is not worthwhile for all our young men to seek knowledge with as much ardor as he did, because only a few can rise to places of important trust. I say let not such sentiments be uttered, especially in this country. For is not the doctrine of hereditary right to rank utterly denounced among us? Are we not all born kings and princes as much as any one? Does not the supreme power emanate from ourselves? Are not the people the sovereign of the land?—Whom they will, they set up, and whom they will, they put down. And surely no one can foretell, which of our youth will hereafter be chosen by their fellow citizens to offices, the duties of which nothing less than the wisdom and understanding of Solomon would qualify them to discharge well.

As every man in the course of events may be called upon to serve the public, every man should qualify himself to do so in the best manner possible. But suppose that ninety out of a hundred of our youth may never be placed in office, be it remembered they are all to take a part in conferring offices; and this, though unhappily it is lightly esteemed, is a duty no less than a privilege of greatest moment. He is not fit to be a freeman, who does not hold his right of suffrage most sacred; too sacred to be prostituted to a party, not less than to the will of an individual usurper! He is not fit to have the right of suffrage, who does not hold his high prerogative in such esteem, that he will not exercise it but upon independent and rational conviction! And such a conviction cannot be formed in a mind that is unenlightened. Can any one deny that the more wisdom an individual may have, the more valuable he will be to the country, though he may never be known in public life?—If all our private citizens were as wise as Solomon, would it not be all the better for themselves and for the nation? Surely so! else are the fundamental principles of our civil constitution false!!

About this Item

The authorship is not given, so perhaps it is written by Charles C. Burleigh, or someone in his family.