The Spirit of Reform

unknown

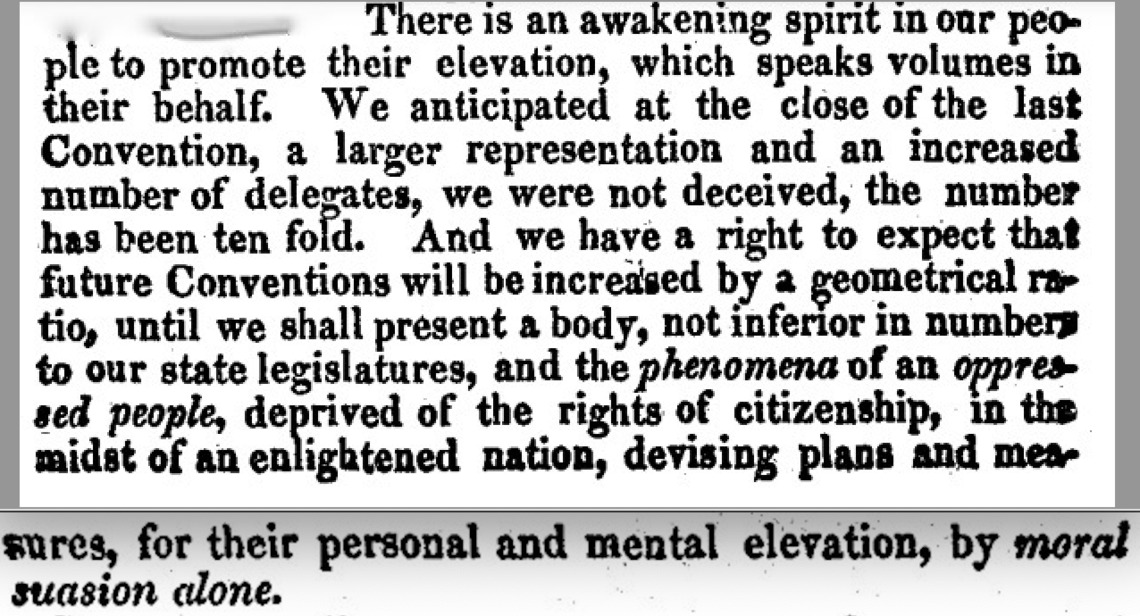

The Unionist 1833-08-08

Unionist content

Transcription

THE SPIRIT OF REFORM.

What is the spirit of reform? What is it that has animated and enabled men from time to time to become reformers, not disturbers, but true reformers; and not religious reformers alone, but moral reformers of all descriptions? Has it not been a sense of independence and personal responsibleness, and of superiority to what are usually termed existing circumstances and the spirit of the age?

A very large proportion of the evil which has always existed in society, may be traced to the want of personal independence, and disregard of personal responsibility. We do not mean by independence that fiery essence of pride and selfishness, which is quick to resent a slight or wrong; which is always ready to meet aggression more than half way; and which delights to show itself in rudeness or haughtiness, as its condition may happen to be low or high. For such independence we have little sympathy and less respect, and so far from thinking that there is a want of it in the world, can only lament that there is such a superfluity. By independence we mean another and a far different thing.—We mean the resolution which adopts, and maintains, and obeys its own standard of right and wrong; which refuses to render an unquestioning homage to the voice of the many; which, being based upon principle, is not to be driven to and fro by the popular breath, even should that breath rise into a whirlwind; which acknowledging allegiance to a higher than any mortal authority, will not forfeit it at the behest of any. This is the independence which leaves to a man his own views and convictions, his own conscience, and his own conduct. Without inciting or suffering him to be forward or boisterous, it makes him steadfast and sure. Without obliging him to feel an uncharitable scorn of public opinion, it offers a rule to his admiration and observance which is alone worthy of serious study, and entitled to his faithful submission,—the great rule of right, the solemn law of God. It teaches him to consider himself as responsible for his thoughts and actions, in the first and highest place, not to the multitude, but to his Maker; and in the second place, not to the multitude, but to his own soul. It leads him into a safer, happier, and more glorious path, than the broad, dusty, soiled and soiling road, which is beaten by the multitudinous and crowding world. It sets his feet and his heart at liberty, and breathes into his soul the consciousness of individual existence and value, and the sense of individual duty.

This is the independence, to the want of which may be traced and referred very much of past and existing evil. Not possessing it, men lose themselves, their accountability, their dignity, all that constitutes them men, in the absorbing mass; where they acquire the color, and motions, and tendencies of the mighty vortex which has engulphed them. Instead of uttering a voice of their own, they wait for an acclamation, and then they join in; instead of having opinions of their own, they listen for the prevalent opinions, and then they repeat them; instead of having a morality of their own, a religion of their own, they are content to be just as moral and just as immoral, just as religious and just as irreligious, as other people; taking the tone of the world around them, which is seldom the highest, and imbibing its sentiments, which are not always the purest. They do not test and try opinions by any self-instituted process. They do not examine manners and actions according to a fixed and exalted standard. They trouble themselves with nothing of the kind. They fall in with the great procession, without inquiring whither it is going, upwards or downwards, to a good end or a bad one; it is enough for them that they are going with it. Thus it comes that so many think evil is metamorphosed into good, when they see the multitude practise it, and good is turned into evil, when they see the multitude slight, or forsake, or forbid it. And thus it comes, that the amount of evil is so vastly increased, because there are so many who blindly and carelessly, or cowardly, without using their own eyes to observe, or their own minds to prove, follow the multitude to do it.

But must we be singular? Must we be eccentric? Must we do nothing that others do; say nothing that others say?—Must we be perpetually quarrelling with society about its usages and habits? No. We are to do none of these things. It is best that we should follow the many in all ways which are indifferent; perhaps it is best that we should follow them in some ways which are inconvenient; but we must not follow them to do evil. “Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil.” That is the simple commandment. It is very true that singularity and eccentricity, when they come from a causeless, wilful, diseased principle of opposition to general custom and sentiment, are no virtues; but even then they partake no more of the nature of sin, than does a servile acquiescence in general custom and sentiment.—Without doubt, public opinion, on most points, is worthy of respectful attention and examination; but, after you have examined it by the great and permanent light within, after you have weighed it in the balance of truth and the gospel, and found it false and wanting, reject and oppose it, and if your decision is to be called singularity and eccentricity, let it be called so, and, in the name of all that is true and holy, be singular and eccentric. We are not required to dispute with the world step by step; we are not required to be solitary and to forsake the world; we are rather called upon to do all the good we can in it, and receive all the good we can from it. But we are required to recognize a higher authority than the world’s will; to obey a more sacred commandment than the world’s law. We are required to form moral and religious principles of our own, and to regulate our commerce with the world. If we will not do this, we shall do evil; for we shall do whatever the multitude does, and the multitude often does evil. The reason why so many follow a multitude to do evil, is, that they want moral independence, and do not hold themselves individually accountable to their own spirit, or to the Father of Spirits.

About this Item

This editorial extols those who live by steadfast principles, rather than ego, conceit, self-interest, or the whims of popular opinion. Thus it obviously addresses, even if obliquely, the situation of the cognitive minority of Immediate Abolitionists. No author is credited; it is interesting to consider if this might be by Charles Burleigh himself.