Summary - Essays in this Section

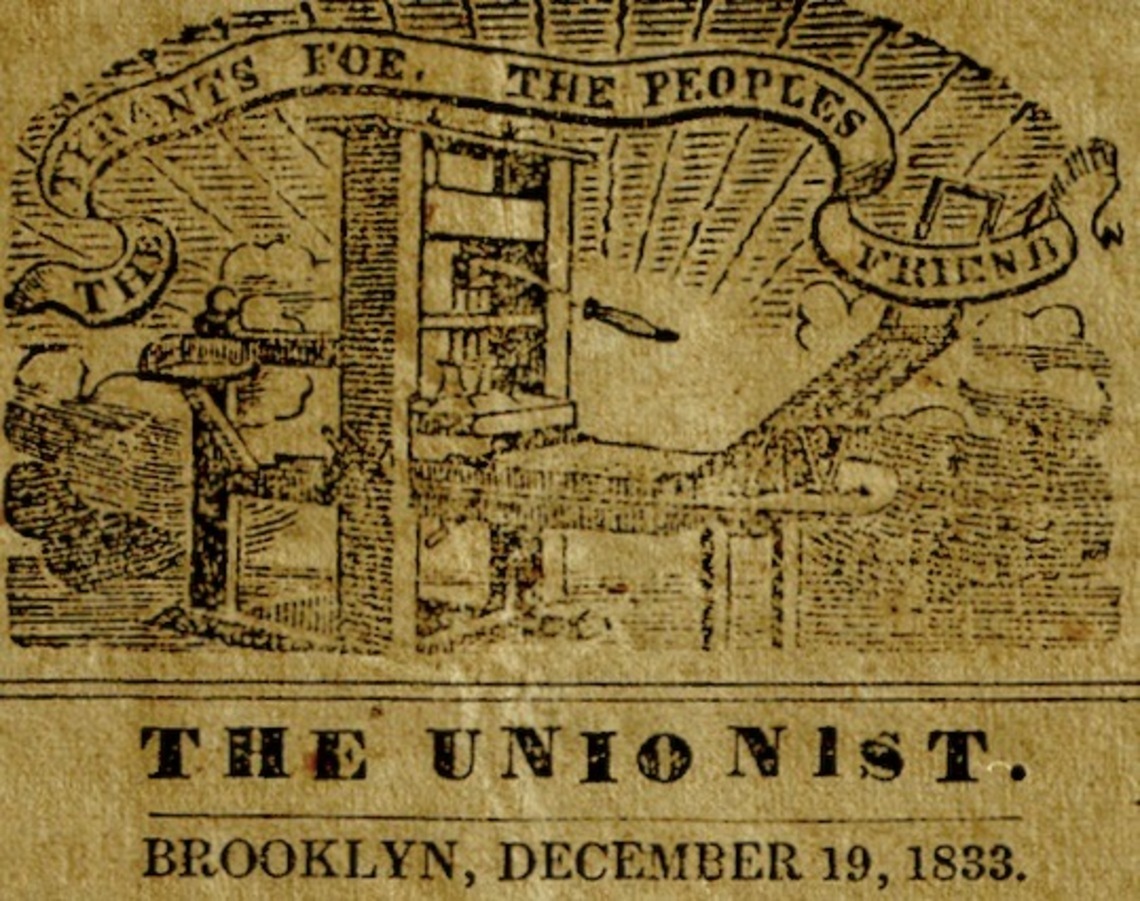

Putting The Unionist back together might seem like a quixotic project. There are many more substantive Abolitionist newspapers that came out after its brief life, and finer examples of the genre of a radical newspaper exist. But in this case, the importance of The Unionist has everything to do with the situation that motivated it. As I argue in my book, Intersectional Pilgrims in Canterbury: Students and Teachers at Prudence Crandall’s Female Academy (forthcoming, University of Illinois Press), the Canterbury Female Academy was a project in which Black women inspired a white woman first. Then that white woman, Prudence Crandall, sought out the organizational assistance she would need from the white male abolitionists, starting with William Lloyd Garrison. Garrison then provided her with introductions to Black ministers and activists, as she looked to encourage students from among their communities. Thus, Canterbury was a cooperative project of Black and white, women and men. The role that white men took in the conflict was at the level of organizing, publicizing, and those duties that, at that time, were functionally limited to white men – such as being lawyers, speakers, and publicists. So reconstructing The Unionist gives us insight into how that network was operating locally, and how public opinion in eastern Connecticut started to turn in Crandall’s favor.

Looked at from a different angle, examining the contents of The Unionist enables us to see a slice of the ideas to which the students at the Canterbury Female Academy were exposed. Abolitionist rhetoric of the sort they were reading was animated by the idea of Freedom. The students watch their own school – its progress, its contestation, its peril – and understand their own historical importance. Likewise, they see the growing chorus of white allies, which had to be heartening – and a fulfillment of David Walker’s prophecy of “What a happy country this will be, if the whites will listen.” Finally there was evidence that some were listening.

The other reason for doing such a study now stems from our time. With the maddening persistence – even resurgence – of racism, we need to remember the power of coalitions like the one that sprouted in eastern Connecticut in 1833-34. Technologically, a project of this nature has become infinitely easier to accomplish. Twenty-first century search technology, coupled with the digitization of newspapers, has made it relatively easy to find reprints of Unionist content in contemporaneous newspapers – though there are plenty more to search. And finally, there is serendipity. An understandable but still regrettable filing error at the Library of Congress meant that two issues of The Unionist had remained unknown to previous researchers. In the twenty-first century, knowledge should always be as free and accessible as possible, and so we are pleased to offer this to scholars, learners, activists, and curious seekers.

For Further Reference

- Chronicling America. Library of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

- Garrison, William Lloyd, editor. The Liberator – full issues 1831-1865 available on line at https://fair-use.org/the-liberator/

- Rycenga, Jennifer. Schooling a Nation: Students and Teachers at Prudence Crandall’s Female Academy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming 2024.

- Rycenga, Jennifer, Nick Szydlowski, et. al. The Burleigh Family of Plainfield, Connecticut: An Anti-Racist Abolitionist Legacy. Digital Humanities project, San José State University, forthcoming 2024-2025.

Published on