Setting and Context - Essays in this Section

In this first academy, Crandall’s white students – for they were all white – enjoyed the school and her teaching. Some may have brought younger siblings with them, including a few boys. But there was another, historically more significant, teacher in the house. The “household helper” was a Black woman from Boston named Maria Davis. She was engaged to marry a local Black man, Charles Harris, and took this job at the Academy while awaiting the nuptials. Davis soon sensed that Crandall was a person with a conscience, and so she began to bring copies of The Liberator to the school to give to Crandall. This radical newspaper had the desired effect. Crandall came to understand the moral stakes and political bankruptcy of slavery; what is more, she immediately grasped the ravages of racism, and how it corroded every prospect for free Blacks. When Maria Davis’s future sister-in-law, Sarah Harris, approached Crandall in September of 1832, asking if she could join the Academy as a day student, Crandall thought about it, consulted the Bible, and opening to Ecclesiastes 4:1 read “So I turned, and considered all the oppressions that are done under the sun: and, behold the tears of such as were oppressed, and they had no comforter; and on the side of the oppressors there was power, but they had no comforter."" She chose to admit Sarah Harris. At first there was no objection, but as the white parents started to hear of this unprecedented integration in what was intended to be a status-based, upper-class-aggrandizing academy, they were shocked and demanded that Crandall dismiss Sarah Harris. When she refused to do so, it became clear that the white parents were prepared to withdraw their daughters from the school, and thus ruin it financially. Yet Crandall stood by Sarah Harris.

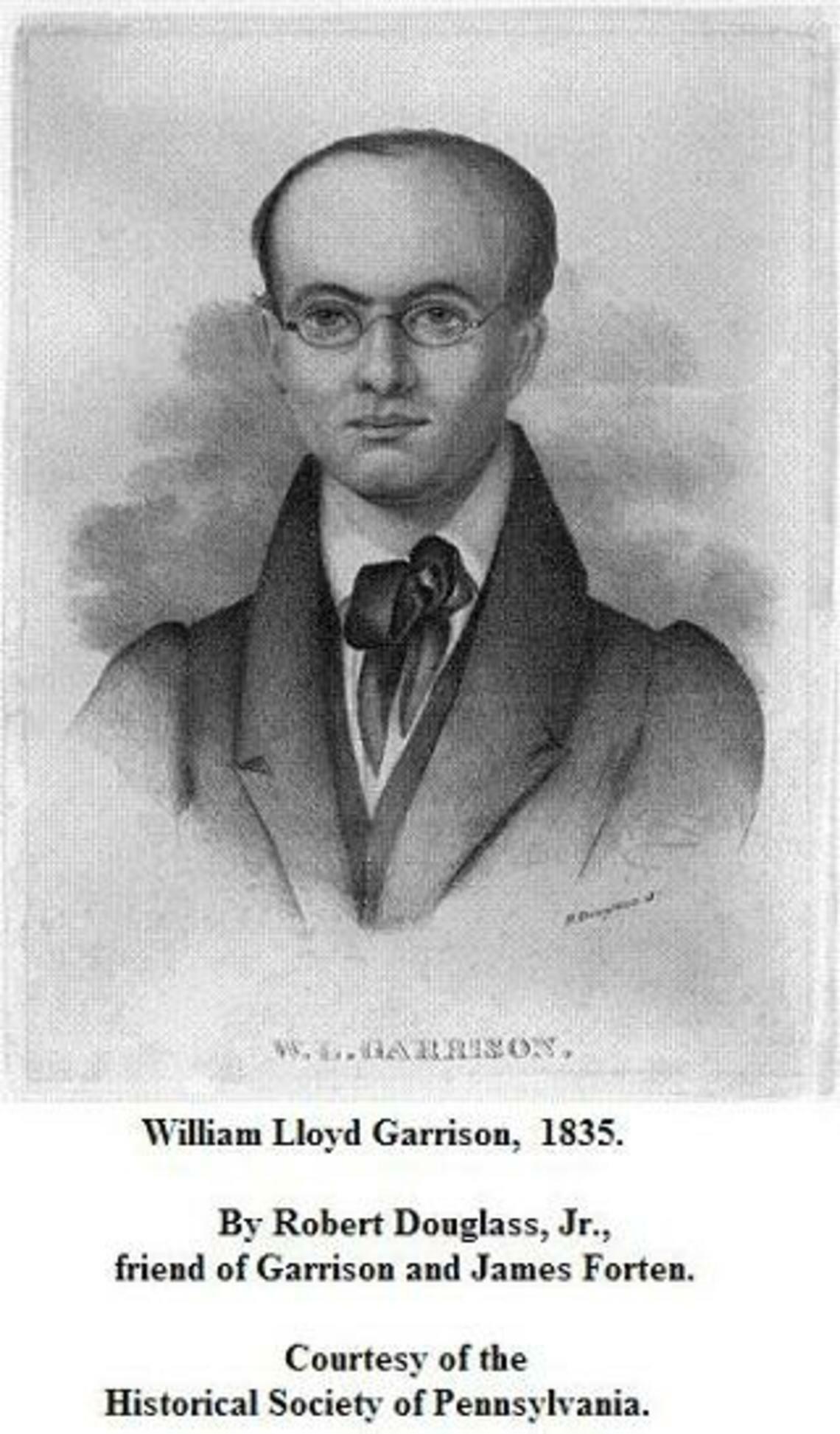

</p>Still, the prospect of the school closing was not one Crandall wanted to entertain, and, as she wrote, she had made the decision to spend the rest of her life benefitting the people of color. She had a creative idea: what if she opened her Academy for Black women and girls only? She presented this idea in a meeting she arranged with William Lloyd Garrison in Boston. He gave her a list of contacts for gathering students, and Crandall was off on a tour that included Providence, New Haven, and New York. She met with numerous Black ministers, and apparently inspired them with confidence in her project. When her plans became known to the people of Canterbury by early February 1833, the white village leaders turned hostile, sending intimidating delegations to her house and scheduling an indignation meeting in early March to insist that the planned Academy for Black women not be allowed in their environs. The village leaders prohibited Crandall from being present, and rudely dismissed her designated representatives – Samuel J. May and Arnold Buffum. Almost simultaneous to this meeting the new list of endorsers for the Canterbury Female Academy emerged. It featured fifteen men’s names: eight Black and seven white. Many of these endorsers would later be referenced on the pages of The Unionist. Just as importantly, it referred to the Black students as “Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color.” Even if these phrases sound patronizing to twenty-first century ears, at the time the terms “lady” and “little miss” were generally reserved for white “respectable” women. The Canterbury white leadership had staked out their ground – exclusion; the Abolitionists had opened their campaign standing their ground — inclusion.</p>

For Further Reference

- Baumgartner, Kabria. In Pursuit of Knowledge: Black Women and Educational Activism in Antebellum America. New York: New York University Press, 2019

- May, Samuel J. Some Recollections of Our Antislavery Conflict. Miami: Mnemosyne Publishing Company, 1969 (1869).

- Mayer, Henry. All on Fire: William Lloyd Garrison and the Abolition of Slavery. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1998.

- Rycenga, Jennifer. Schooling a Nation: Students and Teachers at Prudence Crandall’s Female Academy. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, forthcoming 2024.

- Strane, Susan. A Whole-Souled Woman: Prudence Crandall and the Education of Black Women. New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1990.

Published on