Race - Essays in this Section

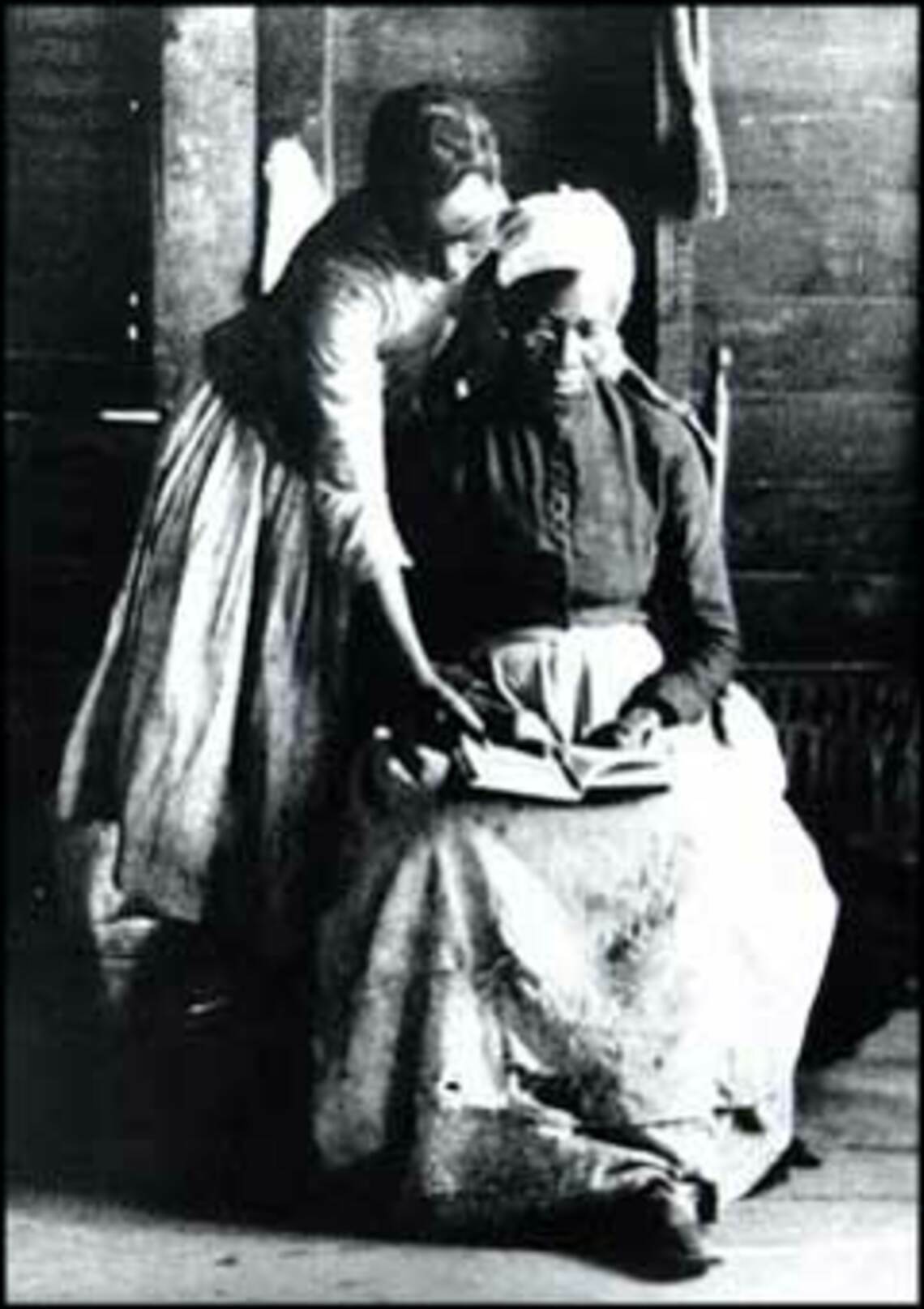

The Canterbury Female Academy did not exist in a vacuum: Black women’s literacy, literature and education were advancing on many fronts. As documented in the nascent independent Black Press and later the Abolitionist newspapers, African-American women formed numerous literary societies. These groups created an academic atmosphere in which members helped each other learn through practice, sharing, and critique. The literary societies demonstrate that Black women in northern urban settings longed to expand their horizons, preparing the way for their eventual entry into places like Oberlin and Black colleges after the Civil War. Black women’s self-development in intellectual matters was not for individual self-aggrandizement: skills gained through education functioned as community resources.

The term “literary” did not hew to a narrow definition. Reading material often came directly from the Black and Abolitionist press. In the pages of The Liberator, Garrison consistently praised the work of literary societies during the early 1830s. Philadelphia’s (male) Colored Reading Society, founded in the 1820s, maintained subscriptions to the Genius of Universal Emancipation and Freedom’s Journal. There is evidence, too, that schools with Black students used the African-American press as reading material; the New York Free School held a subscription to Freedom’s Journal.

The Philadelphia Female Literary Society, formed in 1831, followed a suggestion from Simeon S. Jocelyn that the Black women there hold “mental feasts.” The accomplished women of the Forten, Bustill, and Douglass families, among others, created an elaborate formal structure, with a constitution, officers, and a structure for anonymous critique. New York’s Phoenix Society – an educational project spearheaded by Crandall endorser Samuel Cornish – also featured “mental feasts” for sharing original work. The success of such intellectual events was lauded in the 1833 Black National Convention report.

“Mental feasts” consistently combined themes of elevation with abolition. One of the finest examples of this comes from September 1832, commemorating the Female Literary Society’s first anniversary. The eloquence and confidence of the writer-speaker testifies to the larger goals of female education. She states that the continuity of the Literary Society itself aids abolition and the enslaved, for “our interests are one… we rise or fall together.” She is equally keen to use literacy against racism: “with the powerful weapons of religion and education, we will do battle with the host of prejudice which surround us. The structure of the Literary Societies included anonymous submissions and group critique. Learning linked to political activity became a strategy for developing the intellectual capabilities of African-Americans and of women. The New York Female Literary Society, launched in 1834, held fairs and raised funds for the publication of The Colored American, showing the unity of causes and the absence of separation between individual education and community advancement.

The parallels between these literary societies, replete with mental feasts and abolitionist undertakings, and Canterbury are immense. Similar to the literary societies, the students at Crandall’s school were reading The Liberator and The Unionist– in effect, watching their own struggle rivet the nation. Black women’s self-consciousness concerning the advantages to themselves and their community in developing and displaying their mental capabilities means that the students’ goals at Crandall’s Academy were intended to serve individual, communal, and political goals. These young women knew for what they were striving.

For Further Reference

- McHenry, Elizabeth. Forgotten Readers: Recovering the Lost History of African American Literary Societies. Durham: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Peterson, Carla L. Black Gotham: A Family History of African Americans in Nineteenth-Century New York City. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

- Porter, Dorothy. “The Organized Educational Activities of Negro Literary Societies, 1828-1846.” Journal of Negro Education 5:555-576 (1936).

- Sterling, Dorothy, editor. We Are Your Sisters: Black Women in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Norton, 1997 [1984].

- Winch, Julie. ““You Have Talents—Only Cultivate Them”: Philadelphia’s Black Female Literary Societies and the Abolitionist Crusade,” in Jean Fagan Yellin, editor. Women and Sisters: The Antislavery Feminists in American Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989.

Published on